Grace Fox, MPP, Tribal Healthcare Policy Analyst, Native Nations Center for Tribal Policy Research

Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) is a program of the Indian Health Service (IHS), located in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tribal citizens, or members of federally recognized Indian tribes, may receive healthcare services from an IHS or tribal healthcare facility. When services patients need are not available or accessible at IHS or tribal healthcare facilities, the PRC program authorizes and pays for eligible healthcare from providers that are not IHS or tribal providers.

This report describes how PRC is structured and administered and describes its rules, workflows, and funding. This report first outlines core program elements—eligibility and PRC Delivery Areas (PRCDAs); notification and documentation timelines; medical-priority levels; alternate-resource coordination; staffing and claims processes; and funding constraints. It also summarizes key findings from federal audits, tribal Congressional testimony, and recent policy initiatives related to PRC administration.

This report emphasizes the PRC process as it relates to cancer care. Cancer is an increasingly important public health priority in Indian Country. As described in this report, American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations experience later-stage diagnoses, lower screening participation, and higher mortality than the U.S. population overall. Further, cancer incidence—or the rate of newly diagnosed cancer cases—exceeds that of other populations for lung, colorectal, and kidney cancers. These patterns underscore the importance of timely access to cancer care for AI/ANs.

As this report describes, tribal citizens may seek cancer care from various providers. One way is through the PRC program. In the cancer context, PRC supports oncology diagnostics and treatment, and the timing of PRC authorization and processing can directly affect how quickly abnormal screens move to diagnosis and treatment for tribal citizens. Specifically, this report examines how PRC intersects with cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. The analysis then links these structural features to specific points along the cancer care pathway where delays or gaps are most likely to occur, with attention to national and Oklahoma-specific cancer data for AI/AN populations. Because many of these services are delivered by non-IHS/tribal providers, PRC often functions as the authorizing and paying mechanism when local specialty capacity is unavailable or not accessible in a timely way.

Tribal decision-makers may consider several policy options for addressing the PRC process with an emphasis on cancer care pathways. The options are organized around tribally led, sovereignty-driven strategies grouped into six thematic areas, including: 1) self-determination and self-governance under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act; 2) coverage and financial protection, including approaches that expand enrollment in Medicaid, Medicare, marketplace plans, and private group coverage; 3) regional collaborations and partnerships, in which intertribal consortia, academic centers, and national nonprofits pool demand and centralize; 4) service-delivery models, such as mobile screening, shared satellite clinics, and teleoncology, that allow components of cancer care to be more accessible; 5) care coordination, navigation, education, and communication that support timely completion of referred-care steps; and 6) sovereignty-driven federal engagement, in which tribes may use budget formulation, consultation, workgroups, congressional testimony, and coalition advocacy to shape federal decisions about IHS and PRC policy.

For tribal citizens, many steps in cancer care—diagnostic imaging, biopsy and pathology, staging studies, radiation therapy, and subspecialty visits—are often delivered by providers that are not in the Indian Health Service (IHS) and are not tribal providers. If tribal citizens, defined as citizens or members of a federally recognized Indian tribe (tribe or Tribal Nation), receive healthcare from IHS or tribal facilities, they may be referred to non-IHS/tribal providers, or sometimes referred to in this report as outside providers, when cancer care they need is not available.[1] Access to these referred oncology services is managed through the Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) program.

PRC is the IHS program, located in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), that purchases eligible care from outside providers when: 1) no IHS or tribal direct care facility exists; 2) an IHS or tribal facility cannot provide the required emergency and/or specialty care; 3) a facility’s capacity is exceeded; or 4) supplementing alternate resources is necessary for comprehensive care.[2] PRC functions as a bridge between IHS and tribal facilities that provide direct care (health services delivered in-house at an IHS or tribal clinic or hospital) and outside providers in the broader health care system. PRC operates under federal regulations that establish eligibility and medical-priority criteria and, as the payer of last resort, requires the use of other available coverage before PRC funds are applied.

This report describes how PRC functions in practice with emphasis on cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Federal oversight and program rules identify structural features that can affect whether and how quickly patients can obtain referred services at different points in their cancer care. PRC eligibility and administrative requirements—including residency rules tied to a tribe’s designated PRC Delivery Area (PRCDA), medical-priority categories, alternate-resources verification, and documentation/notification timelines—can influence the timeliness of access to specific services (e.g., scheduling cancer screenings or initial oncology visits). These requirements may also affect approval or payment for referred services (e.g., ineligibility due to residence outside a PRCDA, or denial pending proof of other coverage).

Tribal Nations may choose to respond to PRC-related cancer challenges through multiple, interconnected strategies. This report first describes how PRC is structured and administered, then summarizes federal oversight findings and recent policy developments, and reviews cancer burden data for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations with emphasis on Oklahoma. It then presents tribally focused policy options for consideration, grouped into the following thematic areas: 1) self-determination and self-governance; 2) coverage and financial protection; 3) regional collaborations and partnerships; 4) service-delivery models that bring oncology care closer to patients; 5) care coordination, navigation, and education; and 6) sovereignty-driven federal engagement on IHS and PRC policy.

For the purposes of this report, the below terms are defined and are generally applicable throughout this report. Other terms may defined for specific purposes throughout the report as well.

Direct Care – Direct care refers to medical and dental services provided through direct patient–provider interaction, which occurs on-site at either IHS or tribal health facilities. This differs from Purchased/Referred Care, which supports eligible care delivered by outside providers through referrals and is subject to eligibility rules and funding availability.

IHS Direct Service – IHS direct service refers to care delivered to tribes through federally operated IHS facilities and service units. This differs from tribal health clinics, which are facilities operated by tribes under Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act agreements using IHS funding. Both provide direct care to eligible AI/ANs and, when needed services are not available locally, may initiate referrals for PRC-supported outside care.

PRC Referral (Provider Referral) – A PRC referral (used interchangeably in this report with provider referral) is the clinical request initiated by an IHS or tribal clinician (or clinic staff on the clinician’s behalf) to obtain medical or dental care outside the IHS/tribal facility because the needed service is unavailable locally or capacity is exceeded. A referral starts PRC review but does not guarantee PRC payment.

PRC Application – A PRC application is the patient-facing eligibility and documentation process used by some programs to establish or confirm baseline eligibility for PRC (e.g., PRCDA residency, tribal citizenship or descent documentation, and alternate-resource coverage). Not all programs use the term “application” formally; in many settings, it refers to the packet of forms and supporting documents PRC staff require to confirm eligibility and process a request.

PRC Approval – PRC approval is the decision by the PRC program/ordering official that a specific requested service meets PRC requirements (including eligibility, medical necessity, medical priority/funding availability, payer-of-last-resort/alternate resources, and notification/timeliness rules). PRC approval generally means PRC is prepared to authorize the service for potential payment, subject to scope and conditions.

PRC Purchase Order or Authorization – A PRC purchase order is the formal authorization instrument issued by PRC that specifies what is approved for outside care—typically including the patient, provider/facility, authorized services, dates or units/visits, and any limits or conditions. In practice, “authorization” and “purchase order” are often used together because the purchase order documents and tracks the authorization. This report uses purchase order, PRC authorization, or authorization interchangeably.

PRC Payment/Reimbursement – PRC payment/reimbursement is the payment made to the outside provider (or fiscal intermediary) after care is delivered and a claim is submitted. Payment occurs only if the claim matches the purchase order/authorized scope and all conditions are satisfied (including alternate resources billed first and required documentation/notification on file). PRC approval and authorization do not guarantee reimbursement if later conditions are not met.

The federal trust responsibility to provide health care to AI/AN people arises from treaties, statutes, and the government-to-government relationship between tribes and the United States. Through foundational laws, such as the Snyder Act of 1921, Congress began establishing health services for AI/AN people.[3] In 1954, Congress transferred health functions from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) to the U.S. Public Health Service.[4] In 1955, Congress created the Indian Health Service (IHS), within the U.S. Public Health Service (now within HHS), and began operationalizing the federal government’s trust responsibility for AI/AN health care.[5] In 1976, Congress reaffirmed this responsibility in the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA).[6]

In practice, this federal trust responsibility was often carried out through IHS direct service facilities, which are federal medical facilities that provide direct care to tribal citizens. Direct care refers to medical and dental services provided on-site at IHS or tribal health facilities, involving direct patient-provider interaction within the facility.[7] However, direct care facilities were not always equipped to meet the full range of patient needs. For complex or high-cost conditions, patients often needed to seek care beyond IHS and tribal facilities, making referred care a necessary part of the system.

The IHCIA formally created and authorized Contract Health Services (CHS) to purchase care from non-IHS/tribal providers when specialty direct care services were not available at IHS or tribal facilities, capacity was exceeded, or comprehensive care required supplementation of alternate resources.[8] In 2014, Congress changed the program name from CHS to Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) to reflect both the purchase of outside services and the referral processes that precede payment.[9]

PRC therefore sits at the intersection of IHS direct service facilities or tribal medical systems and the general U.S. health care network, with eligibility and priority rules established in statute and regulation. PRC eligibility and priority rules will be discussed in more detail in the “PRC Eligibility” section of this report. Next, this report discusses PRC administration in IHS direct service facilities and under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act authorities as each intersect with the PRC program.

PRC is administered under uniform federal requirements, primarily the IHS regulations at 42 CFR Part 136, which establish general principles and requirements for carrying out Indian health programs.[10] However, day-to-day operations differ depending on whether services are delivered by an IHS direct service facility or by a tribal health program operating under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA), discussed in more detail below.

As noted above, in IHS direct service settings, the IHS is responsible for providing health care services directly to Tribal Nations and their citizens. PRC functions are typically performed by staff at IHS Area offices (regional administrative units) and IHS Service Units (local IHS facilities or facility networks). These staff screen referrals for unavailable specialty care initiated by an IHS or tribal provider against program rules, including verification of PRC eligibility, assignment of a medical-priority level, and review of medical necessity. It also includes confirmation that alternate resources have been used first because PRC is the payer of last resort. Based on this review, PRC staff issue authorizations to outside providers or, when criteria are not met, defer or deny payment.[11]

For many Tribal Nations, self-determination and self-governance of health services is a pathway to align care delivery with their community priorities, diversify revenue, and reduce dependence on PRC processes. Congress enacted ISDEAA in 1975.[12] As enacted, ISDEAA authorized DOI and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the HHS) to enter into self-determination contracts, sometimes referred to as 638-contracts, with tribal governments so that tribes could operate programs and services for AI/AN people that had previously been administered by the BIA and the IHS.[13] Subsequent amendments in 1992 authorized a Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project within IHS, giving participating tribes the option to enter self-governance compacts for specified health programs.[14] In 2000, Congress enacted the Tribal Self-Governance Amendments (P.L. 106-260),[15] which created Title V of ISDEAA and established a permanent statutory framework for the IHS Tribal Self-Governance Program.[16]

Under ISDEAA Title I self-determination contracts and Title V self-governance compacts, tribes may assume responsibility for health care operations historically run by IHS. Briefly, compacts generally provide greater flexibility than contracts: Title I contracts involve more direct federal oversight of the contracts. Under Title V compacts, tribes may redesign or consolidate programs, services, functions, and activities and reallocate or redirect associated funding without prior IHS approval, subject to ISDEAA and other applicable federal law.[17] In all cases, tribal programs operated under ISDEAA remain bound by the statute, implementing regulations, and the terms of their funding agreements.[18]

Under these same authorities, tribes may elect to assume administration of the PRC program. When a tribe includes PRC among the programs, services, functions, and activities in its ISDEAA self-determination contract or self-governance compact, the PRC funds that would otherwise be managed by IHS are added to the tribe’s funding agreement. The tribe then administers PRC under its own federally approved PRC policies and procedures, consistent with federal law and regulation.[19] Tribal governments may, but are not required to, supplement these federal PRC funds with tribal dollars. For example, tribal dollars may be used to expand eligibility, pay for services that fall outside PRC medical-priority levels, or address shortfalls near the end of the funding cycle. Tribes may also use third-party revenues (such as Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance collections) to support referred care, consistent with their own financial policies.

Under ISDEAA Title I self-determination contracts, tribes may administer PRC but generally do so under the terms of the contract and applicable federal requirements. Title I contracts typically allow less flexibility to redesign program operations or reallocate PRC-related funds without IHS approval.

Under ISDEAA Title V self-governance compacts, tribes have more flexibility to operate their PRC programs. Tribes may manage referral review, authorizations, vendor relations, and claims/payment workflows. They also may tailor operations—such as navigation support, timelines, and memoranda of understanding with local providers—to meet tribally specific conditions.

In both IHS direct service and ISDEAA models, PRC funding is part of the IHS budget that is allocated to IHS Areas and to tribal programs. Specific eligibility requirements must be met by each person needing and applying for PRC assistance.[20] These conditions are discussed in more detail in the next section of this report, “PRC Eligibility.”

PRC eligibility criteria define who can receive PRC assistance. This section first provides an overview of baseline eligibility for IHS services and residence within a PRC Delivery Area (PRCDA). Second, this section reviews authorization conditions that apply to each specific episode of care, including requirements related to timely notification and documentation, funding availability, and medical priority. PRC payment depends on meeting both baseline eligibility and these authorization conditions at the time of referral.

Importantly, PRC is not an entitlement program; in other words, an eligible individual does not have a guaranteed right to PRC payment for any particular service. Authorization of payment is contingent on the following:

· availability of funds;

· compliance with alternate-resource rules; and

· satisfaction of all documentation and notification requirements.

As a result, coverage is not automatic. Denials or deferrals can occur when a patient resides outside the PRCDA, when alternate resources must be used first, when required timelines or documents are not met, or when requested services do not meet applicable medical-priority criteria. PRC referrals are discussed in more detail in the section titled, “PRC Referral Management.”

Baseline eligibility for PRC rests on two foundational elements: citizenship/descent and geography. Citizenship/descent criteria determine whether an individual is eligible for IHS services as an American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) or as another eligible person under federal law. Geography-based criteria determine whether that individual resides within a PRCDA associated with a particular IHS or tribal health program. The subsections below describe how these citizenship/descent and geography requirements operate together to establish baseline eligibility before visit-specific authorization conditions are applied.

PRC eligibility generally begins with eligibility for IHS direct care, with limited exceptions.[21] An individual typically must be able to establish eligibility for IHS services—most commonly through documentation of citizenship in a federally recognized tribe or descent from an enrolled citizen—and this requirement applies whether direct care is provided in an IHS direct service setting or through tribally operated facilities under ISDEAA. Meeting this citizenship/descent baseline eligibility is necessary for PRC referral authorization but not sufficient alone; payment for a specific episode of care also depends on meeting the additional authorization conditions described throughout this section.

Under 42 CFR § 136.12, an individual must provide proof of enrolled membership in a federally recognized tribe or proof that they descend from an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe.[22] As of December 18, 2025, the federal government recognized 575 federally recognized Indian tribes, acknowledged either through an Act of Congress or through the Department of the Interior’s administrative acknowledgment process.[23] Documentation of tribal citizenship or descent is required and is reviewed by the local IHS Service Unit (the IHS facility or network that serves the patient’s community) or by the relevant tribal health program as part of eligibility determination for both IHS direct care and PRC.

PRC coverage may also extend, in limited circumstances, to a non-Indian (i.e., not a member of a tribe) woman pregnant with an eligible Indian’s child (through six weeks postpartum), certain non-Indian household members in a public-health hazard, and adopted, foster, or stepchildren up to age 19.[24] When these special-circumstance categories apply and required documentation is provided, individuals may be treated as eligible for PRC on the same basis as other eligible persons, subject to compliance with all PRC rules and the same funding, medical-priority, and authorization conditions described elsewhere in this report.[25]

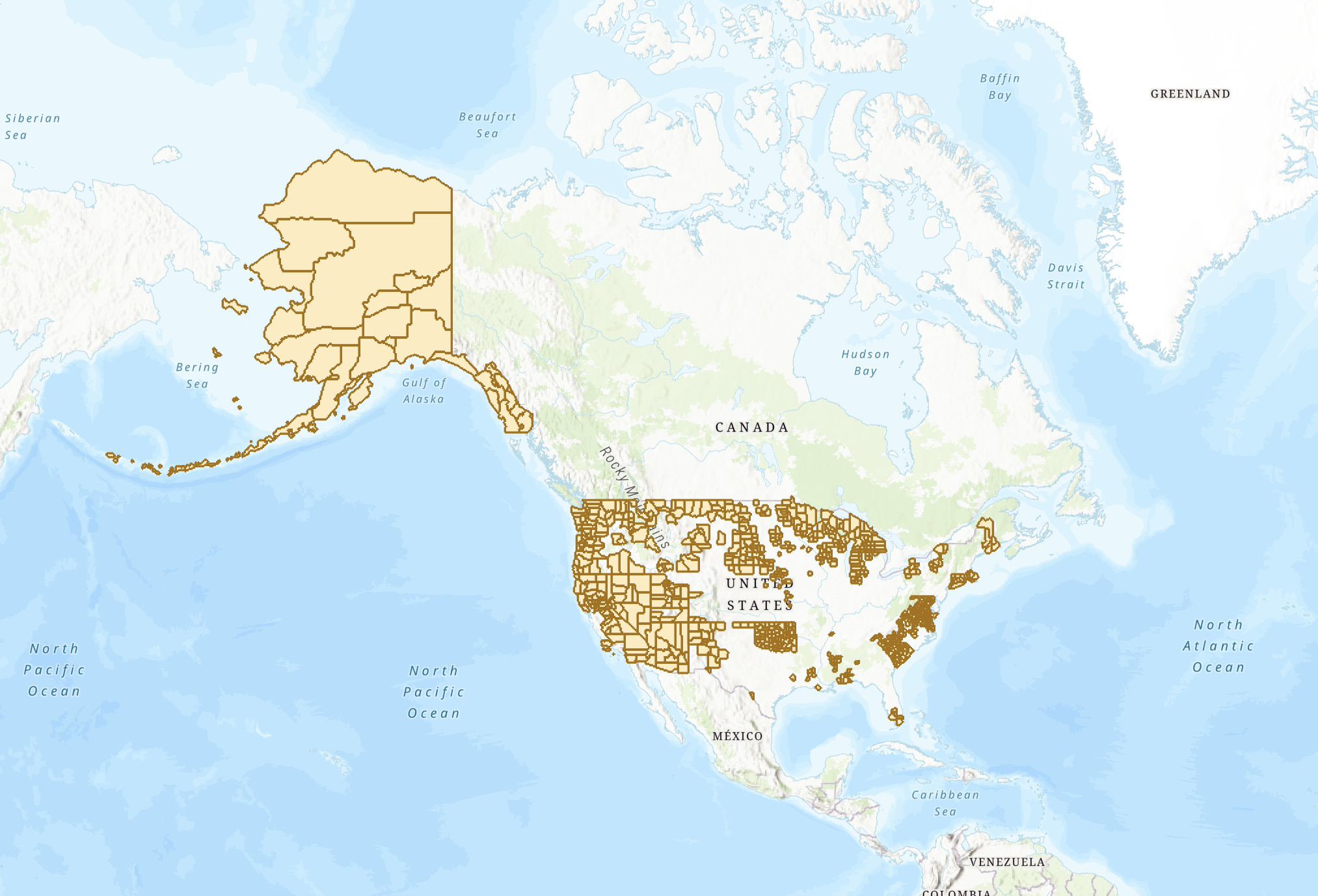

Under 42 CFR § 136.23, PRC residency generally requires that an eligible person live on a reservation or, if not on a reservation, within a PRCDA. In most regions, a PRCDA consists of one or more counties that include all or part of a reservation and additional adjacent counties that are formally designated for PRC purposes. For PRC, “reservation” includes federally recognized reservations, pueblos, colonies, former reservations in Oklahoma, Alaska Native regions established under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, and Indian allotments, as defined in federal regulation.[26] Figure 1 below provides a national map providing a general overview of the delineation of PRCDA designations across the United States.

Figure 1. 2023 Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas from ArcGIS.com.[27] The map shows PRCDAs across the United States. The darker yellow colors generally depict the external boundaries of the PRCDAs, and the lighter yellow color generally depict the land bases within the external boundaries of the PRCDA. All other colors generally depict land areas outside of PRCDAs and are areas not eligible for PRCDA. This map is for illustrative purposes only. Please contact your local IHS area office for specific information about PRCDAs in your area.

In addition to location, PRC residency also reflects the relationship between the individual and the tribe(s) served by the facility. In general, the individual must either be a member of a tribe located on that reservation or in that PRCDA service area, or be another eligible AI/AN person who resides there and maintains close economic and social ties to that tribe (for example, members of other federally recognizes tribes).[28] These provisions apply to eligible AI/AN individuals and, absent an exception in a limited circumstance discussed above, do not extend PRC eligibility to non-Indians who simply reside in a PRCDA. Residency is defined as “where a person lives and makes his or her home” and is documented by acceptable proof—such as housing, utility, or other records—as determined by the local IHS Service Unit or tribal health program. The individual bears responsibility for providing this documentation.[29]

Living outside PRCDA boundaries generally renders an otherwise-eligible patient ineligible for PRC. The residency requirement therefore has implications for patient eligibility, with few exceptions.[30] Notably, using 2020 U.S. Census data, IHS estimates that approximately 87% of AI/AN people live in urban areas and 13% live on reservations or tribal lands.[31] These figures may provide context to whether or not patients are eligible for care.

In most states, PRCDAs are limited to counties contiguous to a reservation, which may cover significant portions of a state but do not encompass the entire state. As a result, otherwise-eligible citizens who live outside PRCDA counties—including those in metropolitan areas where many IHS-eligible AI/AN people reside—are generally not eligible for PRC. In Oklahoma, all 77 counties are designated PRCDAs, providing statewide PRC residency eligibility under IHS rules and Federal Register notices.[32] Even with this statewide eligibility exception, individuals in Oklahoma must still meet the same referral, medical-priority, funding-availability, and documentation requirements as PRC patients elsewhere. PRCDA boundary designation affects residency only and does not waive other PRC conditions.

These geographic constraints have, in some cases, prompted tribes to request expansion or re-designation of their PRCDA so that more of their citizens can qualify for PRC while living, working, or studying outside existing PRCDA boundaries. Congress has, at times, created or re-designated PRCDAs by statute.[33] The IHS Director may also designate or re-designate PRCDAs administratively to effectuate congressional intent—for example, a 2025 Federal Register notice re-designated the PRCDA for the Chippewa Cree Tribe of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, Montana.[34] By expanding the PRCDA to include Cascade County in the State of Montana, the Chippewa Cree Tribe’s PRC-eligible population increased by an estimated 251 tribal members.[35]

Authorization conditions apply to each specific episode of care. Authorizations can be either evaluated at the time a referral for care is made or when a claim is submitted for PRC payment. Even when a patient meets baseline PRC eligibility, payment for a particular visit depends on factors such as timeliness of notification; availability of PRC funds; and medical-priority level. The subsections below describe how these factors operate during the PRC referral and authorization process and how they can affect whether PRC can pay for a given episode of care. The “PRC Referral Management” section of this report describes these referral and approval processes in more detail, step by step.

If an individual seeks outside care that may be covered by PRC funds, the patient (or someone acting on the patient’s behalf) and/or the outside facility must notify the appropriate IHS or tribal PRC office within required timeframes. Notification is the mechanism that allows the PRC ordering official to document the episode, confirm whether the situation is emergency or non-emergency, and determine whether a PRC approval and purchase order can be issued for potential payment.[36] Notification requirements differ for emergency and non-emergency care, and whether individuals meet these requirements can affect whether and how services are authorized.

IHS defines “emergency services” as a condition that, without immediate treatment, could reasonably be expected to result in serious jeopardy to health, serious impairment of bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part. In practice, emergency care includes visits to the emergency room or trauma center in response to life or limb-threatening injuries.

For emergency care, the individual—or anyone acting on the individual’s behalf—must notify the PRC office within 72 hours after emergency treatment begins or a hospital admission occurs.[37] For elders (age 65 and older) and people with disabilities, the notification window extends to 30 days.[38] Notification is typically made by telephone, in person, or through other contact methods specified by the local PRC office; facilities generally provide contact information and instructions in patient materials and on their websites. The notice should include enough information—such as the patient’s identity, dates and location of care, and reason for the visit—for PRC staff to assess eligibility and document the circumstances of the emergency.[39]

IHS defines “non-emergency services” as all care that does not meet the definition of emergency. In practice, non-emergency care includes planned or routine services such as scheduled specialty visits, diagnostic imaging, elective procedures, or follow-up appointments.

For non-emergency care, PRC requires advance notification to the PRC office and prior approval from the IHS or tribal ordering official before receiving outside services in order for PRC payment to be considered.[40] This advance approval is intended to avoid “self-referrals,” circumstances in which patients obtain outside non-emergency care without a PRC referral and may become personally liable for the cost of those unapproved medical services. In this PRC pathway, the advance notification most often occurs through the provider referral process itself: an IHS or tribal clinician initiates the referral, the PRC office reviews eligibility and other requirements, and—if approved—PRC issues a purchase order/authorization before the outside appointment is scheduled.

Because cancer screening, staging, and treatment are typically delivered through planned services, individuals typically receive PRC care through the non-emergency, provider-referred PRC pathway, which is the predominant PRC process discussed throughout this report.

The PRC program is the payer of last resort. Federal regulations establish IHS (including PRC) as the payer of last resort for eligible services—meaning PRC will not authorize or pay for services to the extent another coverage source is available, would be available upon application, or would be available, but for the individual’s eligibility for IHS/PRC services.[41] When PRC authorizes a service, it indicates that PRC will consider payment consistent with these payer-of-last-resort rules after alternate resources have been billed.

42 C.F.R. § 136.61(c) defines “alternate resources” as health care resources other than those of the IHS.[42] These include other health care providers and facilities, as well as federal programs that pay for health services—such as Medicare Parts A and B and Medicaid under titles XVIII and XIX of the Social Security Act—along with state or local health programs and private insurance.[43]

In practice, IHS Service Units and tribal health programs screen referrals for alternate coverage and may require proof of eligibility, enrollment, or application before issuing PRC authorizations.[44] Before PRC payment is authorized, programs must verify and coordinate other coverage—Medicaid, Medicare, Veterans Health Administration benefits, private insurance, and certain state programs.[45] Acceptable documentation typically includes insurance identification cards or eligibility letters; Medicaid or other program approval notices or application receipts; Medicare entitlement notices; VA coordination records; or formal denial notices when applicable.[46] PRC program representatives may assist individuals with enrollment and coordination steps, but individuals are ultimately responsible for furnishing documentation sufficient to substantiate eligibility or application status.

When alternate coverage exists, benefits are coordinated by PRC staff in collaboration with billing and office personnel. In general, the alternate resource is billed first, and PRC considers any remaining balance consistent with program policy and available funds. When coverage is partial or fragmented, staff may need to determine which services are billable to which payer, what deductibles and coinsurance apply, and whether PRC is able to assist with residual balances. PRC decisions may be deferred or denied pending completion of required applications or verifications; in practice, this means that patients who are eligible for other coverage may not receive PRC authorization until they have applied for, or demonstrated enrollment in, those alternate resources.[47]

For cancer, this alternate-resource requirement can be complex, because oncology care often involves multiple providers, repeated services over many months, and separate authorizations for imaging, surgery, systemic therapy, radiation, and supportive care. Tribes have noted that, for time-sensitive conditions such as cancer, this sequence can introduce delays between the clinical decision to proceed with treatment and the point at which all payers have confirmed their roles. These delays may be experienced as administrative uncertainty, repeated requests for documentation, or difficulty determining what portion of care, if any, PRC can support. This alternate resource requirement is a core part of PRC authorization, influencing both the timing of decisions and whether PRC funds are available for a given episode of care.

When funds are insufficient to meet the volume of PRC need within a PRCDA, authorizations are determined on the basis of relative medical need as described under 42 C.F.R. § 136.23(e).[48] In this context, relative medical need refers to how urgently care is required and the potential consequences of delaying or foregoing treatment. Services that address life-threatening or severely disabling conditions are prioritized ahead of those that are routine, elective, or can safely be deferred.[49]

PRC medical priorities are determined during the referral review process, which is when IHS or tribal PRC staff and clinicians evaluate a request for outside services against program rules and available funding. For non-emergency care initiated through an IHS or tribal referral, this review typically occurs after an IHS or tribal provider submits a referral and before the outside service is scheduled. For emergency care, review and authorization may occur after services are delivered, subject to PRC notification and documentation.

PRC medical priorities are usually assigned by IHS or tribal providers, but some routine referrals may be prioritized and authorized by nurse case managers or other designated PRC staff to expedite processing. Some IHS Service Units also use standing orders—pre-approved protocols that allow designated PRC staff to move specified services forward without a separate case-by-case provider order. For example, routing certain high-priority screening or follow-up services directly for authorization once eligibility and documentation requirements are met.

Effective January 1, 2024, IHS revised the Medical Priority Levels framework with the aim of improving consistency and aligning authorizations across preventive, behavioral health, chronic, and acute care.[50] The 2024 update also commits IHS to a systemwide review and update of Medical Priority Levels at least every four years.[51]

Under this updated policy, PRC services are divided into four general categories, each of which is to be given equal consideration:

A. Preventive and Rehabilitative Services;

B. Medical, Dental, Vision, and Surgical Services;

C. Reproductive & Maternal/Child Health Services; and

D. Behavioral Health Services.[52]

Within each category, services are ranked across three priority levels: Priority 1 (Core/Essential), Priority 2 (Intermediate/Necessary), and Priority 3 (Elective/Justifiable).[53] For more information for how the Medical Priority Levels shapes the cancer pathway, see section titled, “How PRC Shapes the Cancer Care Pathway.”

IHS-operated PRC programs are expected to use the standardized priority framework, and recent IHS communications have reaffirmed that cancer-related services—screening, diagnostics, and treatment—fall within the highest priority tier when clinically indicated.[54] In principle, this places oncology services at the top of the allocation framework rather than in lower, discretionary categories.

For tribes operating under self-determination or self-governance authorities, PRC-related policies can look different. While IHS’s medical-priority structure is available as a template, tribally operated health systems are not required to adopt it verbatim. Instead, they may design their own priority frameworks or modify the IHS levels to reflect local values and needs.[55] For example, by explicitly defining how early diagnostic steps, chronic conditions, or behavioral health services are sequenced alongside acute care. In practice, some self-governance tribes mirror IHS priorities for ease of coordination, while others use broader or more flexible categories that emphasize prevention, timely diagnostics, or specific high-burden conditions. This flexibility means that, for PRC pathways, patients may experience different decision rules in IHS-operated facilities compared with tribally operated health programs.

In addition, local interpretation of medical priority criteria shapes how quickly requests move across both IHS-operated and tribally operated systems. Tribes have used consultation, comment letters, and congressional testimony to request clearer guidance and training on how medical priority criteria are applied—particularly where delays can affect time-sensitive care pathways.[56]

Experiences in other clinical areas also illustrate how prioritization can affect timing when conditions are serious but not immediately life-threatening. One Rosebud Sioux patient, for example, reported being denied or waitlisted for PRC funding more than a dozen times since 2018 for an orthopedic problem her physician believed required specialist care.[57] She described living for roughly two years with pain severe enough to require help with daily tasks and believed earlier intervention would have prevented worsening and reduced overall costs.[58] While not a cancer case, it illustrates how the application of medical priority rules may delay treatment for progressive conditions.

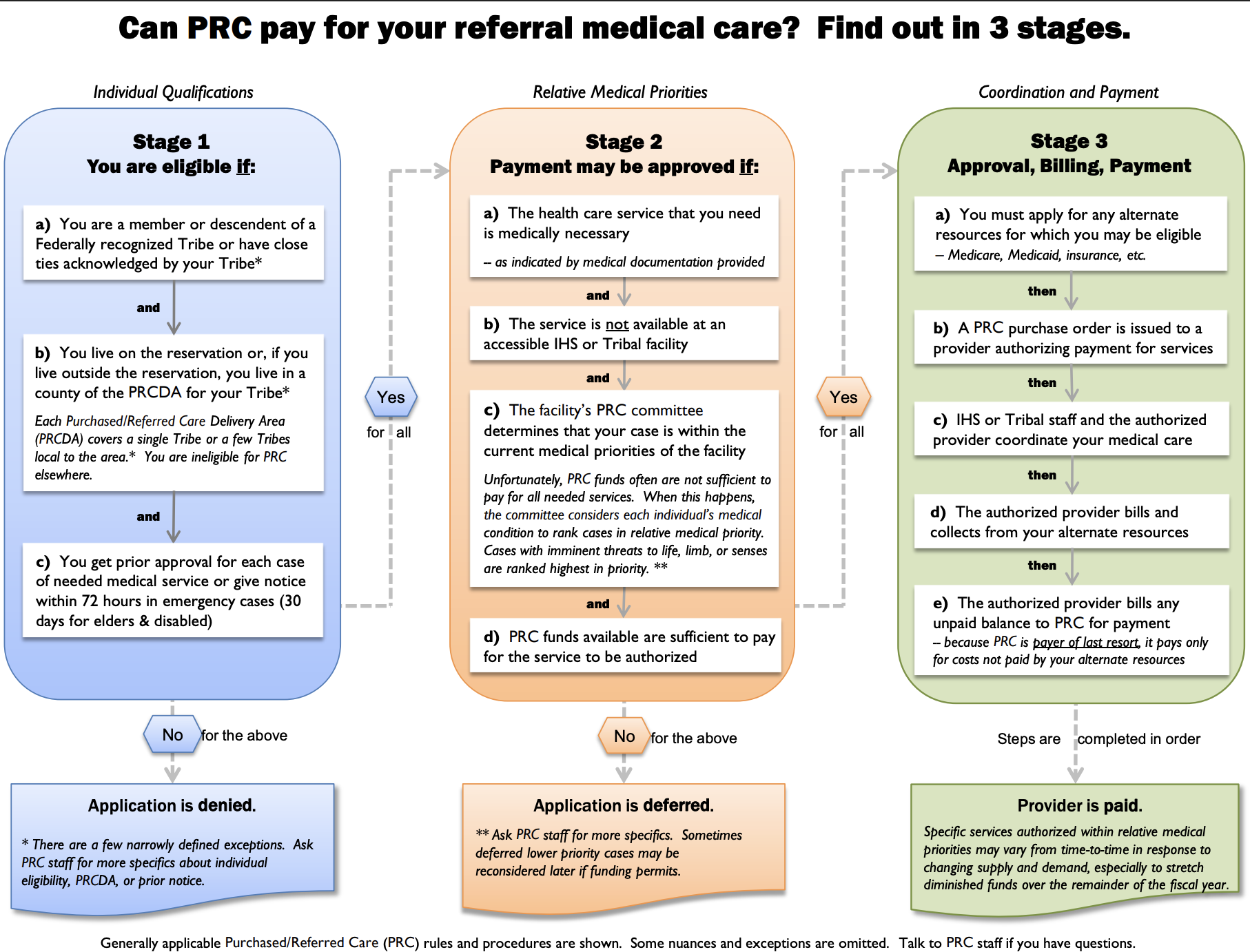

PRC referral management describes how a patient’s need for outside care moves from initial IHS or tribal patient registration to final PRC claims payment. After a patient is registered, referrals for non-IHS or non-tribal services are initiated and routed by IHS or tribal providers, then reviewed by PRC staff to determine eligibility, medical priority, alternate-resource use, and authorization decisions as described in the prior section. This section outlines the key steps in that process—patient registration, referral initiation and routing, PRC referral review and authorization, PRC payment and claims processing, and referral denials followed by reconsideration or appeals. Last, this section describes how these functions interact to determine whether and how PRC pays for a given episode of referred care. Figure 2 provides an overview of the PRC process.

Figure 2. Purchase and Refer Care Eligibility Chart by IHS.GOV.[59]

At each clinic visit, the Service Unit or tribal health program’s patient registration office confirms or updates the individual’s record. The individual is responsible for supplying the following:

1. current mailing and residential addresses;

2. telephone numbers for scheduling and follow-up;

3. emergency contacts; and

4. documentation of tribal citizenship or descent needed for IHS or tribal direct care eligibility.

This registration process is also intended to capture or update information on alternate resources, as previously discussed.[60]

When a face-to-face direct care visit results in the need for services outside the IHS or tribal facility, the clinician issues a referral that is routed to the IHS Service Unit PRC team or the tribal program’s PRC office, respectively. The IHS Service Unit PRC team typically consists of PRC clerks, benefits coordinators, and case managers who work with clinicians to review referrals and determine whether PRC authorization can be issued. In tribally operated programs, PRC teams may include similar roles (e.g., referral/PRC clerks, benefits coordination staff, and case managers), depending on program size and staffing.

A referral is treated as complete when it includes the core information PRC staff need to evaluate eligibility, medical necessity, and coordination of benefits. In most programs, a complete referral: 1) identifies the patient and any known alternate-resource coverage; 2) specifies the requested service and includes clinical information supporting medical need; 3) states the number of visits, days, or units and a brief description of the services requested; 4) names the non-IHS or non-tribal provider or facility; and 5) includes a date of service or date span, when known.[61] Referrals that lack key elements may be considered incomplete and can result in follow-up requests for information or delays in PRC review and authorization. Once a referral is complete, referral routing is initiated.

After a referral is initiated, the PRC administrative team at the Service Unit or tribal health program verifies key requirements, including baseline PRC eligibility, PRCDA residency, notification timelines, completeness of referral documentation, and the status of any alternate resources. Once this initial screening is completed by the PRC administrative team, the case is forwarded to the Service Unit PRC Review Committee (or its tribal equivalent) to determine whether the requested service will be authorized under PRC and eligible for payment, subject to compliance with PRC requirements.[62]

The Service Unit PRC Review Committee is typically composed of clinical and administrative representatives—such as physicians, nurse case managers, PRC staff, and business-office or finance personnel—who are responsible for applying PRC policies to individual cases in light of available funding. Upon receipt of a referral request, the Committee reviews the referral information, confirms the assigned medical-priority level, and determines whether PRC can support payment for the requested services. The Committee may authorize the referral, generally by issuing a written authorization number and defining the scope of approved services (for example, specific procedures, a set number of visits, or a defined date range). It may also deny or defer the request. See section titled, “Referral Denials, Reconsiderations, and Appeals” for more information.

Once a referral is authorized, the PRC program issues a purchase order or payment authorization that specifies the approved provider, services, units (or date span), and any limits or conditions. The outside provider renders care and then submits a claim to IHS for the authorized services, because PRC pays after the primary payer according to coordination-of-benefits rules. This claim typically includes: 1) the PRC purchase‐order or authorization number, 2) itemized charges and clinical coding, and 3) the explanation of benefits (EOB) from any alternate resource billed first.[63]

For IHS-operated PRC programs, authorized outside-provider claims are reviewed and processed for payment by the IHS fiscal intermediary (Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Mexico). Specific pricing rules apply to PRC. For example, pricing rules may include Medicare-like rates (MLR) for hospital and certain facility services, PRC rates (where applicable), or other established methodologies consistent with regulation and IHS policy.[64] The intermediary verifies that the claim matches the scope of the authorization (correct provider, service, units, and dates), that any required referral or notification documentation is on file, and that primary coverage has been billed.[65] If the claim is complete and consistent with the authorization, the intermediary issues payment to the provider. The intermediary also generates a remittance advice that shows the allowed amount and summarizes how the claim was processed. If any billed items fall outside the authorization or do not meet applicable billing or coverage requirements, the remittance advice will reflect those items as nonpayable charges (i.e., “disallowances”).[66]

Timelines for issuing authorizations and making payments are defined in federal PRC regulations and implementing IHS policy. After IHS receives a qualifying notification from a provider, the program must issue either a purchase order or a denial within five working days.[67] When a complete (“clean”) claim is received for an authorized service, payment is generally expected within 30 days.[68] If documentation is missing (for example, the EOB from an alternate resource) or the billed service exceeds the authorized scope (for example, extra units or an additional procedure not included in the authorization), the claim may be pended for additional information, partially paid for the authorized portion only, or denied with a written notice explaining the reason and the applicable appeal or reconsideration rights under PRC rules.[69]

For tribally administered PRC programs operating ISDEAA, claim payments are managed under the tribe’s approved PRC policies and procedures—such as local pricing agreements, vendor enrollment processes, and internal timelines—so long as those procedures are consistent with federal law and regulation. In both IHS-operated and tribally operated settings, however, the core sequence remains the same: authorization → primary payer (if any) → PRC review and pricing → payment or written notice.

If a denial is issued, the written notice identifies the reason(s), which commonly include notification timing, medical-priority determination, eligibility for IHS direct care, availability or required use of alternate resources, Indian descent or membership status, and residency.[70] If a request is deferred rather than denied, the Review Committee does not issue a final decision but instead places the case on hold—often pending additional documentation, completion of an alternate-resource application, or the availability of PRC funds—with the understanding that the referral may be reconsidered when the specified conditions are met.

If PRC payment is denied, the individual is notified in writing and may request reconsideration within 30 days of receiving the denial letter by writing to the Service Unit Chief Executive Officer.[71] If the outcome remains unchanged after reconsideration at the Service Unit level, the individual may appeal to the IHS Area Director and then to the IHS Director. The IHS Director’s decision constitutes final administrative action. Appeals procedures and timelines may differ for tribally administered PRC programs operating under ISDEAA. In such cases, individuals follow the appeals process specified by the tribal health program.

PRC operates within a broader framework of federal oversight and tribal advocacy. Federal agencies review PRC administration through audits, evaluations, and policy guidance that assess how well program rules are implemented and whether funds are used as intended. At the same time, tribes and tribal organizations use consultation, testimony, and formal correspondence to request improvements in PRC oversight and administration, including clearer guidance, more consistent application of rules, and stronger protections for patients. The subsections below summarize key federal oversight findings and describe how tribal leaders and organizations have called for changes in PRC oversight to better align the program with tribal priorities and patient needs.

Federal reviews have identified recurring challenges in the administration of PRC. In April 2020, the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) audited 802,470 PRC claims paid between October 2013 and June 2016, totaling $672.4 million, and drew a random sample of 100 claims to test compliance with nine federal requirements.[72] Tribally administered PRC programs were not part of the review as the audit covered only IHS-administered PRC services.

OIG reported that 18 of the 100 sampled claims complied with all applicable federal requirements, while 82 did not meet one or more standards, such as beneficiary-eligibility documentation, medical-necessity and priority review, timely notification, adherence to PRC’s payer-of-last-resort rule, and timely approval or payment.[73] Based on this sample, OIG estimated that more than 80 percent of the 802,470 paid claims were not reviewed, approved, or paid in full in accordance with applicable requirements of the IHS-administered PRC program.[74]

The audit also examined IHS’s Referred Care Information System (RCIS)—an electronic system used to route referrals and maintain PRC records—and identified control gaps. OIG found that RCIS permitted records to advance without required eligibility documentation and OIG recommended system edits to enforce residency proof at intake.[75] In response to these findings, IHS stated that it concurred with OIG’s recommendations and reported the following actions to address OIG’s review:

1) incorporating residency-verification steps into PRC workflows;

2) providing staff training on medical priority and alternate resources;

3) conducting outreach regarding emergency-notification timelines; and

4) clarifying Indian Health Manual and operational guidance on documentation and payment timeliness.[76]

Earlier federal oversight reached related conclusions about data quality and management. In 2011, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that data used to estimate Contract Health Services (CHS—the precursor to PRC) “need” were incomplete and inconsistent, noting practices that could distort denial counts and hinder reliable estimates.[77] GAO found, for example, that IHS doubled certain categories of reported denials to compensate for missing data and recommended improvements in data quality, program management, and provider communication.[78]

In response, IHS initiated several actions, including establishing an Unmet Needs Data Subcommittee to examine how unmet need is defined and measured for CHS/PRC. The subcommittee’s purview included reviewing data sources and methods, assessing how denials and deferrals are recorded, and advising on options to improve estimates of unmet need. IHS also explored replacing simple tallies of denials and deferrals with a Federal Disparity Index (FDI) approach, which uses an index to compare the level of resources available to IHS and tribal health systems with a benchmark level of funding, thereby estimating the gap between current resources and estimated need. FDI (also described as “Level of Need Funded”) has since been used by IHS in the Indian Health Care Improvement Fund (IHCIF) methodology.[79] Finally, IHS updated its PRC manual guidance to standardize how deferred and denied services are recorded and how unmet need is estimated, drawing on data from the fiscal intermediary (the contractor that processes PRC claims and maintains detailed claims records) and standardized reporting from IHS Areas and tribal health programs.[80] Using both claims-level data and standardized area/tribal reports is intended to improve consistency and comparability across sites and to strengthen the basis for planning and resource allocation.[81]

In addition to federal oversight review, tribal governments request stronger accountability and transparency in PRC administration. In May 2024, the Honorable Cindy Marchand, Secretary, Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in north-central Washington State, testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies, requesting that GAO investigate IHS’s administration of PRC at IHS-managed (direct-service) facilities.[82] The Colville Tribes—served by IHS as a direct-service tribe—reported that persistent mismanagement of PRC funds and processes had led to significant lapses in care, including patient deaths. The Tribes described a case in which a Colville tribal elder needed a referral for ongoing cardiac issues but was unable to obtain timely follow-up because calls were not returned and the PRC purchase order was not issued. Despite repeated attempts and escalation to tribal leadership, the referral remained pending, and the elder died of a heart attack before obtaining access to referred care.[83]

From approximately 2017 to 2022, the Portland Area IHS Office administered the PRC program for the Colville Service Unit remotely, using Area Office staff located in Portland, Oregon, rather than on-reservation personnel—approximately 335 miles away.[84] The Colville Tribes further reported that the Portland Area IHS Office imposed documentation requirements beyond IHS regulations or handbook guidance, for example, the office’s annual submission of utility bills, blood quantum, and enrollment proof for tribal elders seeking referrals. Individuals unable to meet these additional requirements either went without care or obtained care on their own and then faced debt collection when IHS declined payment.[85]

Marchand’s testimony also stated that, during the five-year period of Portland-based administration, thousands of PRC purchase orders accumulated without reconciliation (i.e., being reviewed, matched to claims, and formally closed in PRC records). From 2017-2022, the Tribes estimated that approximately $24 million of the Portland Area’s $33 million (about 73%) in PRC “carryover” reflected unresolved Colville cases—either as unobligated balances or as open obligations (e.g., purchase orders that have not yet been fully processed, paid, or closed).[86] The Colville Service Unit attributed this carryover balance primarily to unreconciled PRC purchase orders rather than to surplus funds.[87] In other words, the “carryover” figure did not necessarily indicate that PRC had money left over; it largely reflected a backlog of purchase orders that were still open or not fully processed, which can obscure whether funds are truly available for new referrals.

Marchand additionally testified that private providers began withdrawing from PRC participation, meaning they stopped accepting PRC authorizations or billing IHS/PRC. Their withdrawal reduced local network options for patients and, according to Marchand, contributed to delays and longer travel distances for care.[88] For these reasons, the Tribes urged Congress to direct GAO to conduct another formal review of IHS PRC management at IHS-managed service units, and to ensure that affected tribal governments are directly consulted in the process. As of the date of this report, GAO has not initiated a review.

Recent legislative proposals and federal initiatives have focused on changes to PRC administration, billing practices affecting PRC-approved patients, and mechanisms for incorporating tribal input into PRC policy. This section highlights three examples: 1) H.R. 1418, the Purchased/Referred Care Improvement Act of 2025, which would modify PRC statutory authority and reporting requirements; 2) the Indian Health Service Director’s Workgroup on Improving Purchased/Referred Care, which convenes tribal and federal representatives to review PRC operations and develop recommendations; and 3) a 2024 joint communication from IHS and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), an independent bureau within the Federal Reserve System, addresses billing and collections practices involving PRC-approved patients. Together, these efforts illustrate how Congress, federal agencies, and tribes are engaging with PRC’s current structure and identifying possible changes through legislative, administrative, and consultative processes.

Recent congressional activity has included proposals to strengthen accountability standards for PRC billing and reimbursement.[89] The Purchased/Referred Care Improvement Act of 2025 (H.R. 1418), introduced in the 119th Congress, would amend section 222 of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act. H.R. 1418 would require HHS to reimburse patients for out-of-pocket costs on PRC-authorized services within 30 days of receiving proper documentation, such as proof of payment.[90] The bill reflects recognition that patients may pay bills themselves to avoid collections while waiting for PRC payments to be processed. The bill requires reimbursement within a defined timeframe, and thus seeks to eliminate prolonged financial risk and ensure that the federal government, rather than patients, bears the cost of approved services. If H.R. 1418 is enacted as-is, patients utilizing PRC would face reduced financial exposure and receive reimbursement for out-of-pocket costs on a more predictable timeline.

The reimbursement provision in H.R. 1418 would not automatically apply to PRC programs operated directly by tribes under ISDEAA compacts or contracts. The bill specifies that these tribal PRC programs are included only if a tribe expressly agrees to adopt the reimbursement procedures.[91] In that sense, the bill primarily governs IHS-administered PRC, while providing an option for tribally operated programs to opt in.

The IHS established the Director’s Workgroup on Improving Purchased/Referred Care in 2010 to strengthen federal–tribal collaboration and provide formal recommendations to the IHS Director on strategies to improve PRC operations, data, oversight, and transparency.[92] The Workgroup reviews input from tribal leaders and other stakeholders to identify program inefficiencies, evaluates the formula used to distribute PRC funds, and recommends operational improvements across IHS and tribal health systems. The Workgroup also functions as an ongoing forum where tribal and federal representatives can discuss PRC eligibility, referral, and payment practices and develop advisory recommendations.

Membership includes two federal or tribal representatives from each of the 12 IHS Areas, providing broad regional representation.[93] The Workgroup typically convenes two times per year.[94] Formal recommendations are submitted to the IHS Director, and once approved, are communicated publicly through “Dear Tribal Leader” letters or similar communications.

On December 12, 2024, the CFPB and IHS issued a joint letter reiterating that individuals whose services are authorized through PRC are not responsible for associated patient cost-sharing (for example, co-pays or deductibles) for those authorized services.[95] The joint communication clarified expectations for providers while reinforcing existing protections for PRC-authorized care. Specifically, the letter notified providers and collectors that attempting to bill or collect from PRC-authorized patients may violate federal law and credit reporting standards, including the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, and the Fair Credit Reporting Act.[96]

This letter followed a CFPB report released the same day, which found that Native American communities are almost twice as likely as the general population to have medical debt in collections and that these debts are on average 33 percent higher for Native American communities.[97] The report attributed these figures in part to improper billing and delayed PRC payments, which can push authorized debts into collections even when patients are not responsible.

Cancer is an increasingly prominent public health priority in Indian Country. In July 2025, Robyn Sunday Allen (Cherokee Nation), CEO of the Oklahoma City Indian Clinic, stated that “cancer has become the new diabetes in Indian Country.”[98] This section first summarizes the national cancer burden among AI/AN populations, then provides Oklahoma-specific context for tribal communities statewide. It then outlines data collection consideration and how cancer statistics for AI/AN populations are generated, interpreted, and compared across regions and over time. It also describes insurance, economic, and geographic factors that shape cancer outcomes.

Across the United States, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (NH AI/AN) populations experience higher cancer incidence, later stage at diagnosis, poorer survival, and

more limited access to medical care than non-Hispanic White (NHW) populations.[99] Analyses report elevated incidence for several sites—including lung, colorectal, liver, stomach, kidney, and cervix—alongside higher proportions of advanced-stage disease and lower survival for many of these cancers.[100]

Regional variation in cancer incidence and mortality further illustrates differences in cancer burden among NH AI/AN communities. CDC data from 2025 indicates that “[t]he overall rate of getting cancer is more than twice as high among NH AI/AN people in the Southern Plains region (612 per 100,000 people) compared to the Southwest region (294 per 100,000 people).”[101] Patterns of cancer type also differ by region. Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among NH AI/AN populations in nearly every IHS region, except the Southwest, where it ranks fourth after colorectal, kidney, and liver cancers. Stomach cancer also shows notable regional variation—ranking fourth among NH AI/AN people in Alaska but only sixth in the Southwest and not appearing among the top ten cancers in several other regions.[102]

According to the 2024 Cancer Burden in the State of Oklahoma, the state’s overall age-adjusted cancer incidence rate is comparable to the U.S. average (~1.2% difference), yet its mortality rate is 19.6% higher. This data suggests a gap between diagnosis and survival outcomes.[103] For example, one Oklahoma-based study noted that the 33 states report higher incidence, and of that number, three report higher mortality—demonstrating the possibility of an incidence–mortality gap.[104]

Oklahoma is home to 38 federally recognized tribes and the country’s largest AI/AN alone population (14.2%).[105] AI/AN alone means that an individual only identifies as American Indian or Alaska Native and not another race. If including AI/AN alone or in any combination, meaning an individual identifies as both AI/AN and another race(s), the state has the second-largest AI/AN population in the United States, after California (9.1%).[106]

Between 2014 and 2018, 9,852 new cancer cases and 2,995 cancer deaths were recorded among the state’s AI/AN population.[107] As an example, by comparison, the age-adjusted cancer incidence rate for NH AI/AN residents was 612.6 per 100,000, compared with 439.9 per 100,000 for NHW residents—about 1.4 times (≈39%) higher.[108] Mortality rates were higher: 262.8 per 100,000 for NH AI/AN versus 176.5 per 100,000 for NHW—about 1.5 times (≈49%) higher.[109] Prior figures demonstrate a similar pattern: from 2000 to 2018, incidence among NH AI/AN Oklahomans increased by roughly 14%, while NHW incidence remained approximately stable (~–1%); NH AI/AN mortality rose by about 4% and NHW mortality declined by about 14%.[110]

Data limitations—such as racial misclassification in cancer registries and vital records—may also understate AI/AN cancer data. Understanding cancer outcomes relies on consistent and accurate data collection. A key consideration in monitoring AI/AN cancer burden is racial misclassification and under-documentation of AI/AN identity in cancer registries and vital records.[111] If AI/AN patients are recorded as another race in medical records or on death certificates, overall incidence and mortality rates for AI/AN populations may be underrepresented.

The inconsistent classification may contribute to a range of underreporting. For example, one 2014 data analysis reported that inconsistent classification of AI/AN race on death records ranged from 1.2% in one IHS Area to 30.4% in another.[112] Further, linkage of cancer registry data with IHS records showed that 77.6% of AI/AN cancer cases in PRCDA counties and 39% of AI/AN cancer cases in non-PRCDA counties were correctly classified as AI/AN.[113] This suggests that AI/AN race misclassification is substantially more common in non-PRCDA counties, and that cancer burden may be undercounted for AI/AN people—particularly outside PRCDA areas.

To address potential data misclassification, national analyses often limit datasets to NH AI/AN residents of PRCDA counties, where linkage with IHS records improves racial classification.[114] This approach seeks to reduce misclassification bias and improve the credibility of regional comparisons. However, it may exclude AI/AN people living outside PRCDA boundaries, AI/AN individuals who are not citizens of a federally recognized tribe (a political classification), or those who do not interface with IHS or tribal health facilities. Analyses conducted in this way may provide more accurate data for the included population but present a national picture that is less than complete.

Improving data quality typically requires collaboration among tribal health programs, IHS, and state cancer registries, including regular record linkages and feedback processes to correct misclassified or incomplete entries.[115] Tools such as the U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualization platform—which integrates data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program—help illuminate trends by region, cancer type, and sex.[116] But experts suggest ongoing refinement is needed to capture the full cancer burden across Indian Country.[117]

More comprehensive, representative data could provide policymakers with a more accurate understanding of cancer disparities, which in turn may contribute to better-aligned screening, prevention, and treatment resources directed to tribal communities that face additional structural barriers to timely cancer care.[118]

Patterns of health coverage, income, and geography help explain some of the observed differences in cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, and mortality for AI/AN populations.[119] These factors do not determine cancer occurrence on their own, but they may influence exposure to risk factors, participation in screening, and the timing of diagnosis and treatment, which in turn can shape cancer outcomes.

The HHS Office of Minority Health, drawing on 2024 American Community Survey (ACS) estimates, reports that 16.2% of NH AI/AN people are uninsured (compared with 8.2% in the total U.S. population); about 44.8% have private coverage (compared with 67.2%), and roughly 49.1% rely on public programs such as Medicaid or Medicare (compared with 36.8%).[120] These coverage patterns are associated in the broader cancer literature with differences in preventive care use, cancer screening participation, and timeliness of diagnostic evaluation, which may contribute to higher rates of later-stage diagnosis and poorer survival in many AI/AN communities.

Economic differences may also influence cancer risk and outcomes. According to 2024 ACS estimates, the median 12-month household income for NH AI/AN households was $54,485, compared with $81,604 for all U.S. households—about 33% lower.[121] Nineteen percent of AI/AN families live below the poverty line (versus 8.5% nationally), and unemployment among AI/AN people (7.8%) is higher than the national rate (4.5%).[122] Public health literature suggests that lower income and higher poverty can contribute to cancer disparities by increasing exposure to certain risk factors (e.g., commercial tobacco use, occupational hazards, and food insecurity) and by creating barriers to prevention and early detection (e.g., screening access, transportation, time off work). These same constraints can also reduce a patient’s capacity to initiate and sustain recommended cancer care (e.g., completing diagnostic workup, attending treatment visits, and follow-up), which can affect stage at diagnosis and survival.[123]

Geography may further contribute to cancer disparities, particularly for AI/AN individuals in rural or reservation communities that are far from cancer screening and treatment facilities and may have limited or no access to public transportation. Studies of rural and frontier areas have linked longer travel distances and transportation constraints to lower screening participation, delayed diagnostic workup, and differences in treatment patterns, which can translate into regional variation in cancer incidence and mortality.[124]

When viewed together, coverage, economic, and geographic conditions provide important context for interpreting cancer statistics in Indian Country and for understanding why some tribal communities experience higher cancer burden than others. Other clinical, environmental, and social factors may also contribute to observed differences in incidence and survival rates. These variables shape the environment in which PRC and other referral mechanisms operate; later sections of this report examine how PRC-specific rules interact with these broader factors to influence the timing and continuity of cancer care.

A primary way PRC shapes the cancer pathway is through the PRC medical priority framework. As noted previously, under the PRC medical-priority framework, services are grouped into four categories and ranked by priority. Because cancer screening and oncology-related services fall primarily within Categories A and B, this section describes those two categories in detail.

Within Category A: Preventive and Rehabilitative Services, the current medical-priority levels list Screening Mammogram, Screening Sigmoidoscopy/Colonoscopy, and Lung Cancer Screening Low Dose CT (smoker) as Core (Priority 1): Essential services.[125] Within Category B: Medical, Dental, Vision, & Surgical Services, Cancer Diagnosis/Treatment is similarly designated as Core (Priority 1): Essential.[126] This reflects an explicit policy choice to place both cancer screening and the main components of diagnostic workup and treatment in the highest priority tier when PRC funds are allocated.

From the beginning of the cancer pathway, PRC can shape whether and where screening occurs. When an IHS or tribal clinic does not have on-site capacity for mammography, colonoscopy, or low-dose CT lung screening, a clinician issues a referral to an outside facility. That referral enters the PRC process described earlier in this report: the PRC office verifies baseline eligibility (including residence within a PRCDA), confirms that the requested service is a Priority 1 cancer screening, and determines whether alternate coverage such as Medicaid, Medicare, VA benefits, or private insurance is available. For these planned (non-emergent) screenings, prior authorization is generally expected before the outside appointment, and patients are typically responsible for furnishing residency documentation and information about any insurance enrollment or applications. When screening is performed on-site at an IHS or tribal facility, PRC is not involved in payment, but PRC may still be needed for follow-up services if the facility does not provide downstream diagnostics or treatment.

When a screening test—whether performed on-site or at a PRC-authorized outside facility—shows a concerning result, similar steps apply to diagnostic workup and treatment. Referrals for diagnostic imaging, biopsy and pathology, staging studies, surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, or other oncology services are reviewed under the same medical-priority and payer-of-last-resort rules.

In combination, PRC rules and workflows provide additional context for interpreting the epidemiologic patterns described earlier. Even when cancer screening and treatment are classified as Priority 1 under PRC guidelines, administrative and funding constraints may still affect the timeliness and continuity of care.

Tribal decision-makers may consider various policy options for consideration that are tribally led and sovereignty-driven strategies. This section offers options that consider ISDEAA authorities; coverage and financial protection; regional collaborations and partnerships; service-delivery models; care coordination, navigation, education, and communication; and sovereignty-driven federal engagement.

In the cancer context, self-determination contracts and self-governance compacts can give tribes tools to reduce avoidable delays within referral pathways. For example, tribes may consider the following:

1. standardizing oncology “clean referral” packets that meet PRC documentation needs up front (PRCDA residency proof, alternate-resource verification, and medical-priority justification);

2. codifying expedited internal timelines from abnormal screen to biopsy and first specialty visit; and

3. formalizing vendor relationships with regional cancer centers (such as bundled rates, scheduling assurances, and rapid-response appointment slots).

Tribes may also choose to dedicate navigation staff to manage handoffs across facilities, link travel and lodging supports to referral milestones, and reinvest third-party revenue (including Medicaid, Medicare, and VA agreements) into screening capacity, diagnostics, and treatment partnerships. These efforts can reduce exposure to PRC bottlenecks and hasten time to care.

Depending on tribal priorities, self-determination and self-governance arrangements may be used to redesign eligibility and referral workflows, cancer navigation, and care coordination functions in ways that reflect local definitions of success.[127] Tribes could rely on compacting and contracting to stabilize staffing, shape oncology partnerships, and structure local responses to high cancer burden.

While final federal funding decisions rest with Congress and federal agencies, tribes may exercise their sovereignty to shape how self-determination and self-governance authority is used in practice. These options could include:

1. negotiating compacts and funding agreements that support oncology-relevant priorities;

2. forming or joining consortia to increase bargaining power with payers and cancer centers; and

3. using tribal consultation, intertribal coordination, and data on referral delays or cancer outcomes to inform federal decision-making.

Tribes may consider how governance, financing, and service design can be organized under tribal control to address cancer-related needs when models are adapted to local infrastructure, workforce, and payer realities.

Intertribal consortia and external partnerships are approaches Tribal Nations have used to expand specialty capacity, pool resources, and shorten the pathway from abnormal screen to treatment, including for cancer care. In different regions, tribes have developed collaborative structures that centralize certain functions—such as specialty contracting, housing and travel, navigation, and data—while maintaining community control over local care. For the 38 federally recognized tribes located in Oklahoma, these models illustrate several possible ways to organize cancer-related services at a regional scale, in parallel with existing PRC processes.

Intertribal consortiums are most often mutually beneficial collaborations or partnerships that can include Tribal Nations, health centers, academic institutions or other organizations working together to achieve shared goals.

For example, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) is the largest, most comprehensive tribal health organization in the United States, serving a statewide AI/AN population.[128] It operates within the Alaska Tribal Health System as a tribal-governed consortium that partners with regional tribal health organizations and delivers statewide services, including specialty care at the Alaska Native Medical Center and systemwide public health and infrastructure programs.[129] Text Box 1 provides more information on ANTHC.

Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) Services and Functions |

ANTHC operates in the Alaska Tribal Health System providing the following services or functions: · Its central facility serves as a multi-specialty referral hospital that provides acute, specialty, primary, and behavioral health services, including oncology and hematology. · It coordinates functions that support specialty care for rural patients, including lodging near the hospital, organized travel support, telehealth connections back to village clinics, and prevention programs. · Its unified governance structure supports growth in third-party billing revenue, longer-term investments in specialty services, and integration of cultural healing practices alongside quality-improvement efforts. |

Text Box 1. Created by Native Nations Center for Tribal Policy Research. Cite: Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, “ANMC Fact Sheet: Alaska Native Medical Center: High-Quality, Culturally Sensitive Health Care,” January 2024, https://anthc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/2024-ANMC-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

For cancer care, local tribal clinics conduct screening and initiate workups, the Alaska Native Medical Center provides staging and treatment, and follow-up often returns to home clinics through teleoncology—reducing repeated long-distance trips and clarifying handoffs between community sites and the specialty hub.[130] Elements of this model—for example, centralized contracting and pricing, shared housing and travel support for referred patients, and a consistent teleoncology infrastructure—could be adapted to multi-tribe settings outside Alaska, with adjustments for geography and payer mix.

In another example, the South Puget Intertribal Planning Agency (SPIPA) illustrates a different emphasis: coalition infrastructure organized around cancer control rather than a shared hospital. Founded in 1976 by the Chehalis, Nisqually, Shoalwater Bay, Skokomish, and Squaxin Island Tribes, SPIPA supports cancer-related prevention and control efforts across member tribes, including education, coordination, and community-based programming. SPIPA’s data-guided coalition approach may provide a framework for a statewide or multi-region cancer control network with common metrics, shared navigation capacity, and a joint registry.

SPIPA provides the services listed in Text Box 2.

The South Puget Intertribal Planning Agency (SPIPA) List of Services |

SPIPA provides the following services: · Provides intertribal planning support and direct services, including health programs. · Provides breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services through a consortium of Tribal clinics, supported in part by federal early-detection funding. · Offers a long-range Cancer Control Plan that expands screening (including colorectal campaigns). · Includes navigation services that follow individuals from outreach through diagnostic resolution. · Works to strengthen tobacco prevention and cessation efforts. · Maintains a regional tribal cancer registry to guide planning. · Provides a registry and navigation functions that may shorten delays between an abnormal test and treatment initiation. |