Home

Abstract

Introduction

Theoretical Background

Rationale and Hypotheses

The Interactive Model

Method

Discussion

References

Appendices

The Wild Card

Effect and Military Retention:

Latent Social Identities in an

Interactive Organizational Commitment Model

Rationale and Hypotheses

(Continued)

An interactive model

H4. The interactive model will predict a member's commitment to a specific organization more precisely than the specific propensity model.

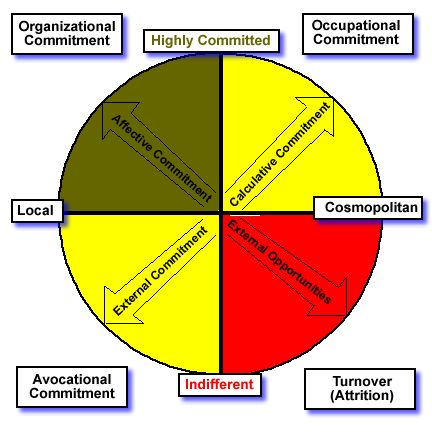

Figure 4. The Interactive Model

Many antecedents and factors have been identified which may influence commitment. If individuals have unique values, then the value they place on different rewards and inducements will vary from individual to individual. Being able to graphically represent the effect of the interactions between these variables on commitment would be useful. Figure 4 represents a model that allows researchers to visualize the effects of manipulating the variables.

Exchange and instrumental reward systems are cosmopolitan traits (Toonies, 1947). Therefore, calculative incentives are likely to be more effective on the cosmopolitan end of the scale. Fraternity and freely met needs are local traits. Therefore, affective incentives are likely to more effective on the local end of the scale.

Marital status has been consistently confusing as an antecedent to commitment. In some studies it related to high commitment. In others, is has been cited as a cause of low commitment. This model offers an explanation by introducing a new factor beyond organizational and occupational commitment called avocational commitment. People exist beyond the scope of an organization. A model that ignores the meaning of that is useless. Avocational commitment functions in the same way as occupational commitment in that on one hand it draws commitment away from the organization, and on the other it can also help to keep an individual in the organization. For example, if work demands keep a committed family member from being with the family too much, this will reduce commitment to the organization. However, when an individual must support a family, that person is less likely to exit the organization. The factor that would be necessary to convince the person to actually leave would be sufficient external opportunity.

External opportunities have been repeatedly supported as an important factor in organizational commitment (Barnard, 1938; Larwood, Wright, Desrochers & Dahir, 1998). An excellent opportunity outside the organization can lure away a moderately committed employee, while another employee with very low commitment may stay if there is no opportunity outside the organization. For example, a lifetime employee with two years to go before retiring with an extensive benefits package has very strong calculative commitment. This individual would tolerate significant conflicts with the organization without seriously considering leaving the organization. However, if the individual were to win $20 million in the lottery, the gravity of the red zone might easily overwhelm the pull of the retirement plan.

Each of the four factors in this model - affective commitment, calculative commitment, external commitment, and external opportunity - pull the member in each of the four directions on the graph. The closer the individual is plotted to the factor, the greater the gravity of that factor on the individual. For example, high calculative incentives alone will only hold an individual in the group as long as no external opportunities offer even higher calculative incentives. With no affective commitment, once those opportunities are introduced, the individual will drop from the yellow zone into the red zone. However, moderate affective commitment will pull the individual back into the yellow on the lower left, and high affective commitment will pull the member back up into the green zone.

Returning to the example of the individual who won the lottery, there is probably no calculative commitment that the organization could reasonably offer to keep the member from migrating from the calculative yellow zone down into the red zone. A strong affective commitment may be able to pull the individual back into the external yellow zone. However, given the lottery-enhanced gravity of the red zone, it would take little in the way of reduced affective commitment to let the individual slide into the red and out the door.

The member's propensity to commit determines the beginning position on the model, thereby indicating which factors will have the strongest influence on the individual. It would be helpful to have an instrument to measure the effects of the other factors independently and together. The authors have devised an Individual Comprehensive Commitment Questionnaire (ICCQ) (Appendix E) to measure an individual's perception of the strengths of each of the four factors, and the tolerances between each. In addition, it should predict the results of changes in each. The results should alter the individual's plot in Figure 4 as follows:

- Stronger affective commitment incentives move the plot up and to the left.

- Stronger calculative commitment incentives move the plot up and to the right.

- Stronger external commitments move the plot down and to the left.

- Stronger external opportunities move the plot down and to the right.

Finally, just as these other factors influence plot of the individual on the model, so should they help to refine the map of the organization. The authors have devised an Organizational Comprehensive Commitment Questionnaire (OCCQ) (Appendix F) to measure an individual's perception of the strength of each of the four factors within an organization, and the tolerances between each. In addition, it should predict the results of changes in each. The results should alter the plot in Figure 4 as follows:

- Strong affective commitment incentives enlarge the upper left quadrant.

- Weak affective commitment incentives reduce the upper left quadrant.

- Strong calculative commitment incentives enlarge the upper right quadrant.

- Weak calculative commitment incentives reduce the upper right quadrant.

- Strong conflicts with external commitments enlarge the lower left quadrant.

- Strong support of external commitments reduces the lower left quadrant.

- Circumstances that increase external opportunities enlarge the lower right quadrant.

- Circumstances that decrease external opportunities reduce the lower right quadrant.

For example, a highly local organization with strong affective commitment incentives, weak calculative commitment incentives, a strong prevention of external commitments, and little impact on external opportunities would be represented by Figure 5. This is a picture of a fire department. A highly cosmopolitan organization with moderate to low affective commitment incentives, moderate calculative commitment incentives, weak support of external commitments, and circumstances that increase external opportunities would be represented by Figure 6. This is an emergency room.

.

.

Figure 5. A plot of a fire department.

Figure 6. A plot of an emergency room.

A communication model

H5. Communication designed to move members into the green zone in accordance with the interactions represented in the model will increase commitment and have a correspondingly positive effect on retention.

To be particularly useful, a model should indicate how to control an interaction. This interactive model of organizational commitment is very much a communication model.

The authors suggest the following communication interactions within the interactive model:

- Individual social identity is adapted through communication.

- Organizational social identity is a product of communication.

- Affective commitment variables are maintained through communication.

- Calculative commitment variables are negotiated through commitment.

- Organizational support for external commitments is expressed through communication.

- Organizational restrictions on external commitments are expressed through communication.

- Organizational preparation for external opportunities is conducted through communication.

- Individual external opportunities are identified through communication.

- Individual external opportunities are negotiated through communication.

Understanding these interactions should provide the organization the ability to positively influence commitment by communicating the most effective recruiting and retention messages for its members and it's organizational model.

DoD Short Course in

Communication

Class 01A

December 7, 2000