|

|

Literary Review

The study of organizations in the social sciences is analogous

to the physical sciences. Organizations are like your body’s

circulatory system. The heart, veins, and arteries make up the

circulatory system. Networks and groups accomplishing a goal form

an organizational system. The corporate world is made up of many

systems called networks or organizations. The U.S. Armed Forces

is a whole entity, a system. The military consists of subsystems,

such as the individual services, the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines

and Coast Guard. Within each of these subsystems are smaller systems--

those commands or units that make up a service. These subsystems

must work together, interact, coordinate and cooperate to meet

their individual service missions and goals.

At times, different elements of the services combine to form other

subsystems or joint operations. Once such example is when public

affairs professionals from the different services, compile Joint

Information Bureaus (JIB). JIBs are compiled of members from different

services and agencies. The JIBs must coordinate amongst themselves

as well as with outside agencies. “The mission of joint

public affairs (PA) is to expedite the flow of accurate and timely

information about the activities of US joint forces to the public

and internal offices” (Joint Publication, 1997, 3-61, p.

v). Combing joint operations involves coordination and cooperation.

Coordination is a key element in organizations and systems and

emphasizes strategies using joint decision making and joint action

making. This process is not always as smooth as it implies. From

a communication perspective, organizations exist “in a world

of colliding events, forces or contradictory values competing

with each other for domination and control. These oppositions

may be internal to an organization because of several conflicting

goals or outside interest groups” (Poole, Van de Ven, Dooley,

& Holmes, 2000, p. 62). Each element of the JIB, as a separate

entity, has differentiated and specialized functions and operate

under their own environments and cultures. Combined, their coordination

is intended to meet one mission or goal, but coordination is hampered

as each element brings different perspectives on how to accomplish

the task.

The military as an organization can be divided into systems and

subsystems; JIBs are one such subsystem of the military. This

literature review looks at the theoretical background of organizational

systems, as they are applied to JIBs.

Organizational Systems Theory

As in many scholarly and scientific approaches, there are an infinite

number of theories in the study of communications. Systems theory

is the most general theoretical approach to communications. A

system is comprised of four elements: 1) objects (the parts, elements

or variables of the system), 2) attributes (the qualities or properties

of the system), 3) internal relationships, 4) an environment (Littlejohn,

1996). It is this synthesis of parts, qualities, relationships

and environments that make up an organization.

Systems theory attempts to understand human behavior within the

context of its systems. A system, for example the military, can

be broken up into suprasystems, such as the services and agencies

which comprise the Armed Forces, which in turn are separated into

subsystems, the individual units and commands within each of the

services. Systems theory is interested in wholes and parts and

their relationships.

The principles of systems theory are: wholeness (in which two

or more subsystems are interrelated, 2) sharing (subsystems are

tied together through shared subparts), 3) synergy (sum of the

system is greater than its parts), 4) entropy (without new energy

the system will run out), 5) self-regulation (systems use feedback

to regulate, correct and improve system functioning), 6) differentiation

(subsystems continue to exist because they provide some function),

7) integration (subsystems are organized in the most effective

ways as to promote synergy and efficiency) and, 8) equifinality

(subsystems start at different places, but end up at the same

destination or final output) (Zuckerman, lecture notes, June 27,

2002). Systems theory emphasizes communication as an integrated

process, not an isolated event.

Systems theory is interested in transformation in organizations.

Transformations are due to the relationships between subsystems.

Relationships cause interactions. These interactions, in turn,

cause changes to the system by adapting to the organizational

environment. Carmack (2000) says two approaches lead to change

in the context of systems: 1) “no single thing can change

without influencing every part of the system in which it belongs,

and 2) change any single part of a system impacts other parts”

(p.2). Change is the catalyst which leads an organization to transformation.

This interdependence on change implies a dependence on relationships

with the organization.

Organizations are open systems. This view emphasizes that organizations

are not enclosed collectives, but open containers, influenced

by their environments. Open systems are seen as “psychological,

social and symbolic constructions through which individuals respond

to their environments” (Taylor, Flanagin, Cheney, &

Seibold, 1999, p. 2). This dynamic perspective on organizations

stressed interconnectedness and the importance of the external

environment. Organizations function by balancing the changing

demands of the environment with control mechanisms that guard

against potentially overwhelming uncertainty (Taylor et al., 1999).

Organizational members create their environments through enactment

or ongoing interaction (Weick, 1969). These environments are framed

within a network of relationships (Monge & Contractor, 1998).

As more networks are created and new relationships are established,

organizations become more complex and uncertain. These complexities

and uncertainties fill organizations with opportunities, and at

the same time are less forgiving of error (Sofaer & Myrtle,

1991). The information age has spurred new ways to disseminate

information. These technological advancements are those increased

opportunities while at the same time adding complexities to systems.

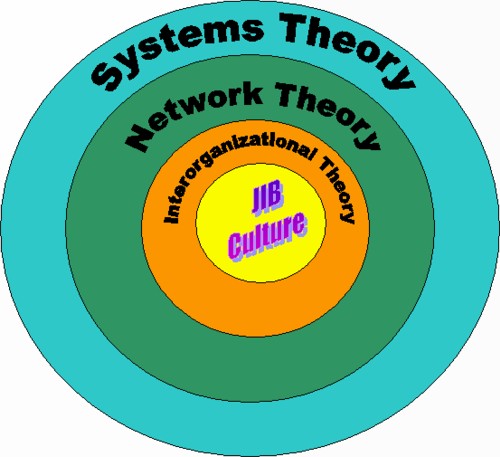

Systems theory explains what comprises a system such as a JIB:

the relationships of a subsystem to the suprasystem within an

organization or system. Systems theories offer a very valuable

perspective on the interconnectedness of JIBs. It allows us to

more carefully examine the individual services perception on how

to interpret “The Doctrine for Public Affairs in Joint Operations”

( Joint Publication 3-61,1997).

One of the most important resources in an organization, such as

a JIB, is information. Network theory explains the distribution

of information in organizations and networks. JIBs, as many systems,

rely on the reception, utilization and transmission of information.

Systems theory does not explain how the organization receives,

utilizes and transmits information. Network theory helps fill

this void by explaining the relationship between networks and

information sharing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Systems Theory As It Applies to JIBs

Network Theory

Information theory is systems meta-theory. Information theory

stresses efficiency in creating, transmitting and receiving messages.

Using information theory as a base, a systems perspective is applied

to networks. Network theory, also known as structural-functional

approach (Infante et al., 1997) or structural-functionalism (Heath

& Bryant, 2000), addresses the means by which social reality

is constructed within an organization (Littlejohn, 1996). Monge

and Contractor (1998) explain communication networks as “patterns

of contact between communication partners that are created by

transmitting and exchanging messages through time and space”

(p.1). Network analysis consists of applying a set of relations

to an identified set of entities. “It is common to use work

groups, divisions and entire organizations as the set of entities

and to explore a variety of relations such as ‘collaborates

with,’ ‘subcontracts with,’ and ‘joint

ventures with,’” (Monge & Contractor, 1998, p.2).

Monge and Eisenberg (1987) integrate three traditions of organizational

studies to explain the structural functionalism of networks: 1)

positional tradition (formal structures and roles in an organization),

2) relational (ways relationships develop naturally and the ways

networks emerge), and 3) cultural (the world of the organization

is created by members in stories, rituals and task work). A key

principle of network theory is that information must be distributed

correctly if the organization is to function properly (Heath &

Bryant, 2000). This distribution relies on links. These links

explain the relationship in an organization or network.

JIBs do not exist as a separate entity, but are linked to a larger

system. In turn, these suprasystems are linked to yet another

organization in the hierarchy. It is a chain bound and held together

by goals the individual members achieve to meet.

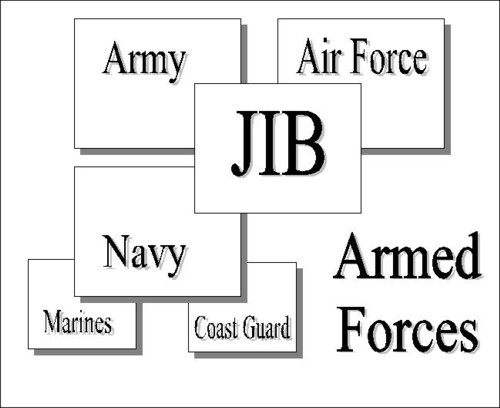

The JIB network is commanded by the “Deputy Joint Information

Bureau Director” (Joint Publications 3-61, 1997, p. III-9).

The JIB director is responsible to the Joint Task Force (JTF)

Public Affairs Officer (PAO) “for all activities conducted

in support of the media relations mission” (Joint Publications

3-61, 1997, 1997, p. III-9). The Commander of the JIB is of the

same service controlling the operations of the JTF. Under the

commander of the JIB is the “Operations Officer” and

reporting to are individual elements of the JIB: 1) administration,

2) media response, 3) media support, and 4) liaison cells. While

principles and doctrines are laid out for the relationships within

a JIB and its relationship with the media, the individual members

that comprise the JIB are from different services. Different services

have varying degrees of interpretations of the same doctrine.

Herein lays another problem with JIBs – network links.

Network links. Communication relationships utilizing

people, groups or organizations rely on network linkages. “Network

linkages are created when one or more communication relations

are applied to a set of people, groups, or organizations”

(Monge & Contractor, 1998, p.3). “Linkages are typically

seen as the means by which organizations manage their dependencies

on resources necessary for organizational survival” (Miller,

Scott, Stage, & Birkholt, 1995, p. 681). Monge and Contractor

(1998) described a two-dimensional approach to interorganizational

linkages based on linkage content and linkage level. The level

dimension has three forms of exchange: 1) institutional linkage

(when information or materials are exchanged between organizations

without the involvement of specific organizational roles or personalities),

2) representative linkage (occurs when a role occupant who officially

represents an organization within the system has contact with

a representative of another organization) and, 3) personal linkage

(occurs when individuals exchange information, but in a nonrepresentative

or private capacity) (Monge & Contractor, 1998). These descriptions

outline the means in which organizations transmit and receive

messages which is critical to the flow of information. Information

is one of the key elements in any organization.

Coordination and cooperation are at the gist of the problems in

JIBs. “Joint” implies coordination --to bring into

a common action. Network theory does not focus on coordinated,

cooperative relationships while interorganizational theory does.

From network theory spawned interorganizational theory (see Figure

2).

Figure 2: Joint Information Bureau Network Structure

Interorganizational Theory

The multiple dyadic relationships between one organization and

other organizations, was the initial focus of interorganizational

theory. The focus then shifted to the behavior of loosely coupled

multi-member organizations within its task environment. With further

evolution, interorganizational theory examines the population

of organizations in an environment. This population is now called

a network. This perspective allows one to identify their place

in the network. It can reveal both the barriers to strategic initiatives

and the opportunities to activate them (Sofaer & Myrtle, 1991).

Interorganizational analysis is concerned with building a smooth,

operating division of labor among agencies. Coordination is the

ultimate variable guiding research. “The impetus for interorganizational

analysis seems to come mainly out of a perceived need to reduce

duplication and overlap of services, to reduce conflicts and tensions

between agencies and to enhance the articulation of services”

(Rogers & Whetten, 1982, p. 141). “Firms are embedded

in networks of cooperative relationships that influence the flow

of resources among them” (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001,

p. 431). Van de Ven and Walker (1984) perceived the need for resources

to achieve organizational goals is the most important factor to

stimulate interoganizational coordination. “Through cooperative

relationships, firms work together to collectively enhance performance

by sharing resources and committing to common task goals in some

domain. At the same time, partners also compete by taking independent

actions in other domains to improve their own performance”

(Gnyawali & Madhavean, 2001, p. 433). “The (dis)advantages

of an individual firm are often linked to the (dis)advantages

of the network of relationships in which the firm is embedded”

(Dyer & Singh, 1998, p. 660) Dyer and Singh (1998) cite four

potential sources of interorganizational competitive advantages:

1) relation-specific assets, 2) knowledge sharing routines, 3)

complementary resources/capabilities, and 4) effective governance.

The very name Joint Information Bureaus, suggest a joint effort.

Joint implies cooperation and coordination. Unfortunately, these

cooperative efforts are hampered by the diversification of tasks

and different perceptions on how to accomplish those tasks. Coordination

and cooperation is a key of the problems in JIBs.

Interorganizational cooperation and coordination. Interorganizational

relations may be characterized by specific practices of coordinating

boundary crossing activities because of the division of labor,

interrelated differentiation of organizational roles and the high

degree of diversification of tasks. Defined by Wehner and Clases

(2000) as “coordinatedness within and between workplaces,

departments and organizations” (p. 4). Cooperation is a

goal-directed and process-related joint activity (Wehner &

Clases, 2000). The actual social processes and dynamics of cooperation

are related to goal orientation, motivation, trust, competition,

conflict, strategies of failure and situational and organizational

preconditions.

Interorganizational cooperation should not be viewed as a direct

outcome of the anticipated and planned forms of joint activity,

because it is strongly influenced by process related experiences

gained in everyday practice when faced with deviations from those

planned (Wehner & Clases, 2000).

Military members often say “stay in your lane,” which

means, stay within your boundaries. When formed, JIBs create a

new organization, distinctly different from the services that

comprise it, producing new boundaries. In a joint environment

such as JIBs, maintaining service uniqueness conflicts with crossing

Interorganizational boundaries.

Interorganizational boundaries. Interorganizational systems

(IOS) (Gregor & Johnston, 2001) and interorganizational relationships

(IORs) (Miller, Scott, Stage, & Birkholt, 1995) are information

systems that span organizational boundaries. The structure beneath

a sector includes rules setting boundaries upon its operation.

These rules restrict the range of alternatives available to the

sector in regards to its policy and administration. Negotiations

and bargaining occur within the range of available alternatives.

Movement beyond these boundaries would be met with various control

measures. At certain stages new rules may become contradictory

to the established ones and contradictory to the entire sector

(Rogers & Whetten, 1982). Boundaries “aid in the delineation

of lines that separate yet join, create linkages yet establish

borders, and frame identities that are both unique and dependent

on others“ (Petronio, Ellemers, Giles, & Gallois, 1998,

p. 589).

Information environments function within organizational boundaries

and emphasize boundary spanning through message routing and summarizing.

Boundary spanning brings information across groups. Message routing

and summarizing reduces the information and may keep boundaries

restricted (Petronio et al., 1998). Coupland, Weimann & Giles

(1991) proposed miscommunication always involved boundary negotiation.

Miscommunication is an indicator of tension in negotiating boundaries

as they emerge and change in interaction. Groups respond to boundary

demands dependent on their abilities and motivations to meet the

demands. (Petronio et al., 1998).

A JIB represents the forces that have joined together in joint

operations to discuss the common effort and represent the roles

of the individual members “An information bureau is a single

point of interface between the military and news media representatives”

(Joint Publications 3-61, 1997, p. III-8). “The mission

of the joint public affairs (PA) is to expedite the flow of accurate

and timely information” (Joint Publication 3-61, 1997, p.

v). Many times the individual services’ interpretations

of how and when to release information causes tensions between

the military and civilian media representatives. Another aspect

of the chain of command or boundaries that govern military networks,

is as Aukofer and Lawernce (1995) outline:

“Secrecy and surprise were paramount

in the division commander’s minds,” said Army Col.

William L. Mulvey, who commanded the U.S. forces’ Joint

Information Bureau in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia during the war. “If

Gen. [John] Telelli of the 1st Cav [alry] did not want a pool

reporter, then his word was supreme. He didn’t get a pool

reporter. He was a two-star general, and I know to salute.”

(p. 11)

On the surface, JIBs may appear to be organized. In reality,

the services display individualistic traits counter to the group

traits. Failure to adopt the traits of the group is a systematic

trait of interorganizational nonconformity.

Interorganizational nonconformity. Some of what is the

bright side of organizations can simultaneously be a dark side.

In addressing the dark side of organizations, Vaughan (1999) outlines

“three types of routine nonconformity with adverse outcomes

that harm the public: mistake, misconduct, and disaster produced

in and by organizations” (p. 271). These are systematically

produced by the interconnection between environment, organizations,

cognition, and choice. Merton (as cited in Vaughan, 1999) observed

that any system of action inevitably generates consequences that

run counter to its objectives. Some types of organizational deviance

result from coincidence, synchronicity, or chance. Organizational

deviance is a routine by-product of the characteristics of the

system itself (Vaughan, 1999).

Communication never takes place in a vacuum and is rarely an isolated

event. JIBs also do not work in vacuums or isolated events. Their

decisions and actions affect other networks, and in turn, these

decisions affect other organizations. The military, while evolved

from American society, adapted American culture to make a separate

and distinct culture all their own. Within the military, the services

have made cultures unique to themselves. Interorganizational culturalism

serves to explain these differences and how problems emerge due

to communication across inter-cultural boundaries.

Interorganizational culturalism. Traditionally, intercultural

communication is related to national culture; in recent years

it has expanded to include organizational culture (Constantinides,

St. Amant, & Kampf, 2001). Just as there are many ways to

define communications, scholars have many disagreements about

how to define culture in organizations. O’Reilly and Chatman

(1996) define culture as “a system of shared values that

define what is important and norms that define appropriate attitudes

and behaviors for organizational members -- how to feel and behave”

(p. 121). Different cultures have different values and beliefs

helping members rank what is important. These rankings influence

how they perceive the function of the organization and the individuals

within it. Different cultures might have different communication

expectations in similar organizational settings. Different cultures

can have different expectations regarding the same document.

Constantinides et al., (2001) defined two treatments of culture:

1) as a variable (an organization has a culture) and, 2) as a

root metaphor -- an organization is a culture. Both of these themes

view organizations existing within an environment. Both study

relationships between cultural elements, across and within boundaries.

Corporate culture reflects the standards of a given industry,

yet these norms arise out of a cultural context. Facts might be

culturally neutral, but the way in which they should be presented

can vary from culture to culture. “Failing to recognize

and address these differences... ...can lead to miscommunication

or offense” (Constantinides et al., 2001, p. 38).

Prototype theory explains how and why members of different cultures

can have different expectations within the same communication

context. Individuals unknowingly use the same term to refer to

different ideas (Constantinides et al., 2001). “All speakers

associate a particular idea or “prototype with a given word

and each ideal is comprised of certain characteristics”

(p. 39). Different cultures can have various expectations of how

the same item is defined. Prototype theory expanded to introduce

strategies of convergence and code switching (Constantinides et

al., 2001). Organizations use convergence to change their prototype

expectations so that group conversations become more similar.

Organizations from one culture use code switching by learning

how to use the prototypes preferred by others. Code switching

is recommended, but users are advised to first learn the audience

by looking for meta-patterns of behavior in a given culture and

then determining the historical reason to anticipate prototypes

of a given audience (Constantinides et al., 2001).

In 1993, Adams saw history as a factor in organizational culture

and introduced “metapatterns” to focus on “the

implicit dynamics of organizational life” (p. 140). Recurring

sequences in a relationship cluster into patterns. These patterns

of relationships in organizations are sometimes overt and transparent,

but many patterns “are tacit” called metapatterns

(Adams, 1993). Metapatterns are constructive, benign or dysfunctional.

“They have a contagious quality, and they do not normally

occur under conscious control” (Adams, 1993, p, 141). Patterns

established in previous interactions, do not have to be intentional

to be repeated. The metapattern spreads contagiously. It is not

the specific behavior or interaction that was repeated, but the

underlying pattern the relationship took.

The significance of metapatterns is that organizations have histories.

Organizations are always in the midst of working out their destiny,

and people within them are “embroidering their own sections

of that destiny through all their relationships. ...those relationships

keep bumping into one another... ...spreading the underlying metapatterns

inherent in them throughout an organization” (Adams, 1993,

142). A person is neither the sole, nor fully conscious author

of their behavior. Relationships experienced in the past are likely

to be patterned. Attention to metapatterns can help see human

interaction as a whole.

Weiss (1992) also saw history playing a part in an organization’s

culture. Every culture sees the world according to that culture’s

heritage and history, immediate contexts also shape meanings.

There are four concepts of interculturalism: 1) instability and

equivocality of messages that cross cultures (a message means

something only within specific cultural context), 2) cultural

construction (culture is patterned ways of thinking, feeling and

reacting but is also open and adaptive), 3) cultural heterogeneity

(understanding ourselves among other people), and 4) dialogic

communication and approaches and attitudes that block it (modes

of intercultural communication, problems with the transmission

model of communication, and intercultural misunderstanding and

miscommunication) (Adams, 1992, p. 2-6).

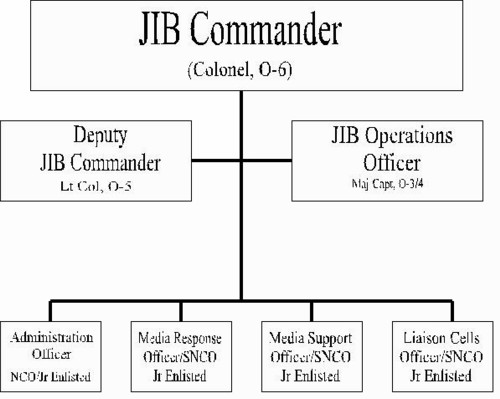

Just as systems theory contends that systems lie within systems,

interculturalism proposes that within each culture exist groups

within groups. The groups are composed of individuals whose attitudes

and actions do not mirror a type but respond to and create a reality

(see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Sample Joint Information Bureau Setup By

Rank

The Nesting of Theories to Explain the Problem in JIBs

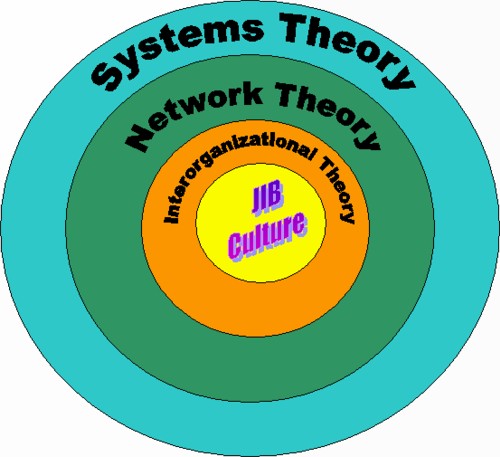

This literature review nests communication organizational theories

to explain the problem within JIBs. Systems theory explains the

relationships in an organization, addressing how a system is comprised

of suprasystems. Suprasystems, for example, the military, are

in turn, are made of subsystems, or the individual services that

comprise the military. The subsystems and suprasystems compile

an entire system or organization. When JIBs are created, they

form yet another subsystem of the military. Unfortunately, systems

theory itself falls short of explaining fully the problem within

JIBs.

Information is a key element in any organization,

especially JIBs, and is exemplified in the name: Joint Information

Bureaus. Systems theory does not address the flow of information.

Network theory does address this key element and helps to explain

the complexities of the information flow. Yet still, network theory

does not address the full breadth of the problems within JIBs.

Coordination and cooperation are at the gist of the problems in

JIBs. “Joint” implies coordination, which in turn,

means to bring into a common action. Network theory does not focus

on coordinated, cooperative relationships, interorganizational

theory does. From network theory spawned interorganizational theory.

So, the problem in JIBs has been identified and framed within

the theory associated with it, interorganizational theory. But

one more question exists, why? Why are there cooperation and coordination

problems? The answer may lie in an interorganizational meta-theory,

interculturalism. Each service compiling a JIB enters into the

operation with their individual service values and cultures. These

values are not discarded because of the joint environment. Different

cultures assign different meanings which create misunderstandings

and miscommunication. Nested within the problem of JIBs, their

lack of cooperation and coordination, are different cultures.

It is the different cultures and the associated different meanings

that create misunderstanding and miscommunication that are the

heart of the perceived problem (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: JIBs As Explained By Organizational

Systems Theory

Summary

Culture Defined in JIBs

Culture within JIBs is based on culture within each of the individual

military services. Webster defines culture as “the customary

belief, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious

or social group.” Culture within JIBs can be a daunting

task to define given the complexities that lie within each of

the military services. Those complexities are magnified once different

groups and agencies work together. Each element that comprises

a JIB, comes with their own background, their own standards, and

their own way of doing things and the environment they each operate

under...essentially each has a different culture.

Culture is a product of meaning. As people take on language, they

adopt a culture that gives them a view of the world (Heath &

Bryant, 2000). To define culture in JIBs, this study uses “values”

as the first criteria. Webster defines values as “something

(as a principle or quality) intrinsically valuable or desirable.”

The military services outline their values as customary beliefs

for each of its members to follow and attain.

Vision is the second criteria used to define culture in this study.

The military operates by regulations, directives, instructions,

and customs and courtesies; these are the military’s formal

ways of doing business, their social form. They stem from history

and evolved to meet the changing needs required of the military.

Change is the only constant to be counted on. From lessons of

the past, the military tries to predict the future. These predictions

mold the military’s focus, creating a vision.

Mission is the third criteria for this study of JIB culture. While

there is overlap of social forms between the services, there are

also distinct differences based on the service’s unique

diversification and specialization. The military’s as a

whole ensures American interests are defended, and each element

of the military are segregated to best meet these means. The Army

covers ground warfare, the Navy protects the seas, and the Marines

combine the two previous service requirements into amphibious

operations. The Coast protects our naval assets as well as ensures

the security of homeland coasts and welfare. The Coast Guard is

not an element of the United States Armed Forces unless Congress

ratifies an act of war. Normally, the Coast Guard falls under

the Department of Transportation. The Air Force ensures our skies

are protected. Each service has a different look to coincide with

their area of expertise. Each uses unique equipment. These material

traits coincide with the unique responsibilities required of each

service, their mission.

The fourth criteria this study used to define culture is network.

Network as defined by this literature review is transmitting and

exchanging messages through time and space (Monge & Contractor,

1998). Network is defined by Webster as “an interconnected

or interrelated chain, group or system.” The formal network

in the military is the “chain of command.” The chain

of command gives the different organizations within the military

a means in which messages are exchanged. Each service and organization

within the military lays out a different network for their respective

public affairs communities. While there are similarities, differences

emerge accounting for different means of message exchanges.

Research Questions

RQ1: Do different service interpretations

or adaptations of Joint Publication 3-61 affect how Joint Information

Bureaus operate/interact in a DoD combined operation?

RQ2: Do interservice doctrine and cultural differences

impede communication flow to both internal and external publics?

RQ3: Do historical case studies reveal that the

improper operationalization of JIBs impede the intended use of

a media pool and the reporting of military actions?

|